[Disclaimer: this is not an official Countdown 2030 Europe position but an opinion piece by the coordinator Joke Lannoye, based on work done by a think tank of Countdown 2030 partners on COVID-19]

The COVID-19 crisis and recovery plans have fostered the emergence of new narratives around ‘building back better’. These are not necessarily new ideas – very often they were already floating around, for example the critiques against the paradigm of economic growth in response to the environmental crisis – but COVID-19 seems to be bringing them together in new and unexpected ways. How are these ideas linked to sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) in global development? And can ‘building back better’ also be a driver for progress in reproductive care and reproductive justice for all?

A changing global development landscape

Globally, the pandemic has highlighted and worsened systemic inequalities, and exposed the widening gap between the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and their implementation. The COVID-19 crisis has shown that health and social protection systems are severely underinvested and not prepared for a pandemic. There has been a lack of investment in public goods such as universal health coverage in recent decades. Further, privatisation of health services has been forced through in many low-income countries, in spite of a significant body of evidence demonstrating the negative effects of privatisation on healthcare systems and vulnerable populations. COVID-19 has had an unprecedented impact on sexual and reproductive health and rights’ organizations and services across the world, caused by either the health crisis itself or by the consequences of the lockdown. It is estimated that the pandemic could result in an additional 49 million women with unmet need for modern contraceptives, and an additional 15 million unintended pregnancies over the course of a year.

Further, the pandemic has caused significant challenges for international development cooperation, partly as a result of triggered protectionism, a swift to a national focus and closed borders. We have also seen an acceleration of the process through which multilateralism is being undermined and setbacks in human rights and democratic governance. In some settings, human rights norms are increasingly framed as being “outside influences”, as governments use the pandemic to intensify authoritarianism. Further restrictions have been imposed on civil society during the COVID-19 pandemic as a number of governments have taken advantage of the crisis to restrict civic freedoms, reduce civic space and criminalize criticism.

On top of the shrinking space for civil society overall, several states and stakeholders have used the COVID-19 crisis to employ a range of tactics to undermine sexual and reproductive rights specifically. Among the examples was a letter sent by the US Acting Administrator to the UN Secretary-General asking to ‘remove references to “sexual and reproductive health” and its derivatives from the UN’s Global Humanitarian Response Plan’. Also, Member Associations of the International Planned Parenthood Federation have reported cases of spreading misinformation, framing the pandemic as an opportunity to reinforce traditional values, increasing discrimination against vulnerable populations, pushing for regressive measures against sexual and reproductive health and rights, and blocking progressive debates on laws and policies.

On the other hand, the global crisis has created opportunities to rethink interdependence and global citizenship. The irrelevance of borders and barriers has become clear – no country can find solutions to the COVID-19 pandemic and its consequences alone. It has brought up common, global challenges that can only be solved through common, global solutions and citizenship. This is needed to achieve a collective consciousness for the defense of global public goods. With global agendas such as the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development at the centre of the COVID-19 response, this could also be an opportunity for systemic change.

Unpacking ‘building back better’: The key ingredients for building more equitable and caring societies

Despite the worrying trends, there is hope that the COVID-19 global pandemic can stimulate the emergence of a new narrative about how to ‘build back better’ through a resilient and sustainable recovery. This unusual situation could offer opportunities to put sustainable development and the SDGs at the center of the recovery process.

According to us, some important ingredients for this recovery to have a positive impact on sexual and reproductive health and rights are: a transformation of our global ‘health architecture’; better global cooperation; implementation of the ‘nexus’ between humanitarian and development; intersectional feminist approaches; and new ways to better include civil society.

- Building back better – a renewed global health architecture

COVID-19 has reminded us about the gaps in the global health architecture overall. Global health mechanisms have been criticised for lack of accountability, transparency and for not involving beneficiaries and affected populations in governance structures. Despite increased efforts of coordination in the global health architecture prior to COVID-19, there has been a lack of harmonisation, coordination and cooperation between different mechanisms and donors, and even donor competition.

COVID-19 can be an opportunity to rethink and re-build the current global health architecture in a way that prioritizes rights-based, people-centered and flexible health solutions – drawing lessons from, for example, the global HIV response. Any future global health architecture should include a multi-sector and system-based approach and broaden the governance space for community and civil society engagement. There could also be greater coordination and cooperation among multilaterals, donors, implementer countries and communities. At EU level, this could start with a new Global Health Strategy (last one dates back to 2010), focusing especially on better coordination (at EU level with Member States but also at global level) and stronger involvement of civil society.

COVID-19 has shown that national health systems must be extended to protect the whole population, especially those currently the farthest left behind. There is no way the post-COVID world will become an equal, just and sustainable one, unless sexual and reproductive health and rights are embedded into Universal Health Coverage. SRHR must remain a central component of essential health services, as governments committed to in the 2030 Agenda and the UHC political declaration in 2019.

- Building back better – rethinking our global collaboration

Within the international development sector, there is a growing recognition that the current narrative, language and structure of development cooperation is no longer fit for purpose and that certain conceptual shifts are needed to make Official Development Assistance (ODA) fit for the 21st century. Some concepts that are increasingly seen as problematic are the exclusive use of growth and country level Gross National Income as economic indicators of progress; the focus on north/developed versus south/developing; and the insufficient focus on addressing inequality.

The COVID-19 crisis is an opening to see development aid in a much wider context of structural power relations and uneven development. The move to ‘building back better’ could be an opportunity to rethink development assistance as part of a systemic response and the promotion of social justice; cooperation that is globally connected but locally driven; and a transformation that devolves currently concentrated global power towards a more democratic state of play.

This evolution of international cooperation could go hand in hand with addressing growing inequality and rethinking the ways global wealth is distributed . In the report by the UN Secretary General António Guterres on responding to the socio-economic impacts of COVID-19, he stressed the importance of a large-scale, coordinated and comprehensive multilateral response. Could this crisis with a more prominent global connectivity also be a chance for a renewed and revived multilateral system with a mandate to help address this?

- Building back better – the humanitarian – development – peace nexus

Central to the Sustainable Development Goals is also the concept of the humanitarian – development – peace nexus. Acknowledging the major step back in achieving the SDGs that COVID-19 is causing, such an integrated approach will certainly become even more fundamental in the coming period. Short-term humanitarian responses alone will not address the longer-term implications of COVID-19 on people’s lives and the need for ongoing support to national health systems, but demands a joined-up ‘nexus’ response.

While traditionally the health sector has focused on the emergency response, the ongoing and future challenge is to take a more proactive approach that builds community and country capacities to prevent emergencies, as well as being prepared for emergencies in advance with timely and effective response and recovery services. ‘Disaster Risk Reduction’ needs to be integrated into the development agenda and include a gender perspective. Although several steps have been taken to integrate a gender perspective and SRHR into health emergency risk management, it is not done systematically in many countries and contexts. With regards to SRHR specifically, it can be an opportunity for increased attention and funding for the transition from ‘Minimal Initial Service Package’ interventions – which are the minimum, life-saving sexual and reproductive health needs that humanitarians must address at the onset of an emergency – to the comprehensive roll-out of services and SRHR programming in humanitarian settings.

- Building back better – through feminist approaches

With feminist approaches to COVID-recovery, we can work towards more resilient, equal, inclusive societies with a transformative perspective to overcome the “corporate power” that has broken health systems and made visible the erosion of our social protection. A feminist approach means addressing the COVID-recovery in a way that recognizes the value of care and people’s sexual and reproductive rights and bodily autonomy, which was compounded by their inadequate access to health care, insufficient financial resources and inequal participation in decision making processes.

In terms of global governance, adopting a feminist approach can bring an alternative vision to the table based on prioritization of human security and socio-economic well-being instead of a traditional militaristic and forceful approach to national security. It can bring more flexible and pragmatic policies based on empirical evidence, science, and long-term perspectives, instead of prioritizing ideology, public posturing, and national political considerations. Feminism can also bring more diverse, inclusive, and equitable leadership and decision-making, challenging heteronormativity, reflecting ground truths and input from marginalized communities, rather than centralized, elitist processes that close down civil society space.

Further, the post COVID-19 context can be an opportunity to change deeply rooted standards around sexuality, femininity and masculinity that currently lead to exclusion, discrimination and human rights violations. Norms and standards can change, and they often do so in response to crisis or forces such as change in economic opportunities. Donors could invest in changing underlying causes of poverty, including in changing harmful gender norms that are severely restricting people’s access to rights and resources.

- Building back better – Improving CSO involvement

Finally, the transformation from physical negotiation spaces and face-to-face meetings to virtual consultations and negotiations might lead to increased or decreased civil society engagement in international and national policy spaces. However, at the same time the COVID-19 crisis might lead to a virtual platform revolution, which could enable more meaningful participation of civil society and other stakeholders in policy processes that they have otherwise not been able to contribute to, due to various obstacles of geographic, financial and political character. This type of transformation would be aligned with efforts needed to ensure a reduction in emissions of greenhouse gasses from excessive air traffic to ‘build back better – and greener’.

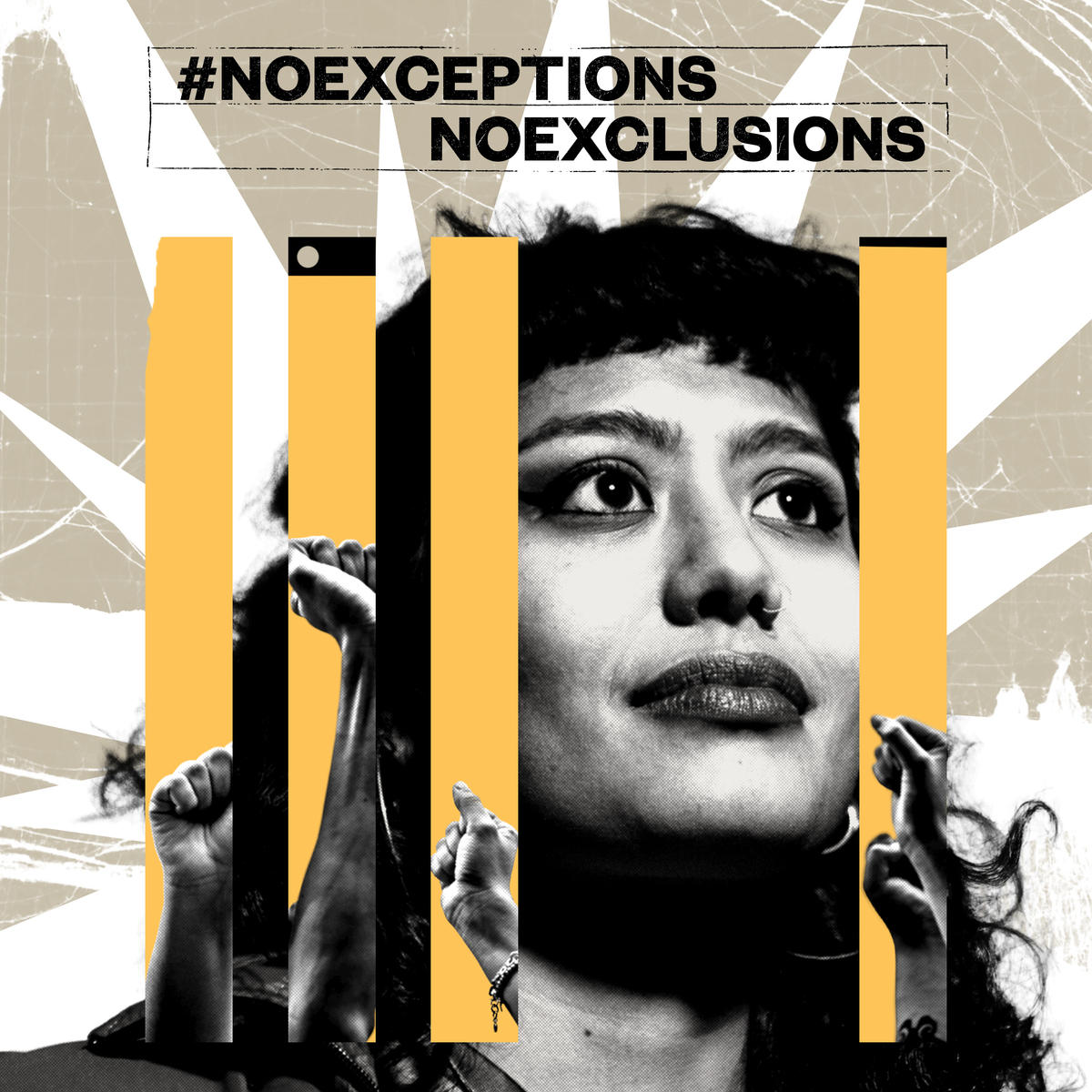

By mixing all the above ingredients, we believe that a fairer, more equitable, caring and inclusive global cooperation and health architecture can be achieved. As a society we must demand our governments do everything possible to protect everyone’s health, with no exceptions, leaving nobody behind in the recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic.